Cultural Competence and Intercultural Mediation in Strategic Communications

A Theoretical Exploration by Eri Estrada

Theoretical exploration of the field of strategic communications has consistently emphasized the role that the social context of active and creative message recipients plays in message cognition, ascertaining that social context, or “culture,” makes an indelible imprint on meaning formation during the process of message cognition. Recognizing that culture plays a significant and unavoidable role in the cognition of messages by active recipients—as all communication is subjective in nature—when operating in an environment in which stakeholders are increasingly culturally diverse as a result of multinational operations, social engagement platforms without borders, and expanding marketplaces, culturally-competent communication is more important than ever, and will become even more valuable as stakeholders continue to demand increased social accountability from organizations, including communications practices that recognize and adapt to stakeholder diversity, and aim for greater inclusion. As such, research on cultural competence and intercultural mediation will positively impact the practice of strategic communication by providing insight on how communications practitioners may be able to bridge intercultural differences when communicating with culturally diverse stakeholders.

Stakeholder diversity has been at the forefront of my career as a communications professional, having worked for various entities within Los Angeles County, the most culturally diverse county in the United States. As a Mexican-American that is bicultural and bilingual, when working for a public Medicaid Managed Care Plan (MCP) in a county where almost half of the population is Latino and almost 80% of those Latinos are of Mexican-origin (Brown and Lopez, 2019), I was regularly tasked with interpreting information between monolingual English speakers and monolingual Spanish-speakers, explaining to executive leadership the cultural nuances that demanded message adjustments.

The State of California Healthcare and Human Services Agency required the MCP to make member materials available in all “threshold languages” found within its service area. A language becomes a “threshold language” when at least 3,000 Medicaid-eligible individuals reside within an MCP’s service area (2017). In Los Angeles County, there were thirteen threshold languages as of the writing of this paper (2020). This speaks to the cultural diversity of the stakeholders I’ve engaged with and why being culturally competent is important to me.

As a bicultural and bilingual actor in an environment that demands culturally competent communications, I am interested in learning how strategic communications actors can become culturally competent in order to achieve culturally competent communications. This paper will touch on existing definitions of cultural competence and how it is achieved; it will also explore research on the role that bi-culturally fluent communications actors, also known as “intercultural mediators,” (Liddicoat and Kohler, 2012, p. 79) play in "bridging" communications between culturally distinct stakeholder groups in diverse environments.

Theoretical Underpinnings for the Role of Culture in Message Cognition

The notion of stakeholders as active, or “creative” message recipients is mentioned by Christensen, Firat, and Cornelissen (2009) when they state that “The reception of corporate messages in not a passive activity through which an audience is trying to figure out what the author meant to convey. Rather, it is a process through which the receiver tries to make sense of a piece of communication by linking it to a context that is familiar or meaningful. Reception, in other words, is a self-referential process of integration in the sense that receivers read meaning into the message by importing relevant information from their own world. Reception, therefore, is always a creative process that cannot be planned or managed by the sender” (p. 213).

Culture is a “context” that is “familiar or meaningful” to the recipient, as are the social norms and expectations established by xyr culture. Researchers further claim that message cognition is not just a creative process for individual recipients, but that in developing perceptions about an organization, “there are sociological processes involved, as organizational reputation is socially constructed among a collectivity of organizational observers” (Lange, Lee, & Dai, 2011, p. 162), so the referential process that occurs when a recipient interprets a message is not just “self-referential” as described by Christensen et al. (2009), but also group-referential. Lange et al. (2011) state that this group-referential process results in organizational reputation being “idiosyncratic to a given set of perceivers” (p. 163).

Lange et al. (2011) ultimately connect the concepts of familiar context and idiosyncrasies shared by a set of perceivers to culture when they state that “organizations and their observers together are immersed in cultural systems from which standards for judging corporate favorability are socially constructed,” (p. 160) such favorability standards are based on how well an organization is believed to “conform to practices deemed culturally desirable,” where expectations “defer depending upon the set of perceivers sampled” (p. 165). Hallahan et al. (2007) also highlight the role that culture plays in the interpretation of messages when stating that “meaning involves questions such as how people create meaning psychologically, socially, and culturally” (p. 23). Sohn and Lariscy (2012) emphasize the relevance of message recipients’ culture in interpreting messages and evaluating organizational reputation when they state that “people may use different logic systems when evaluating firms depending on the context of assessment, which includes…its symbolic conformity with cultural expectations” (p. 4). Because culture establishes social norms, when Cornelissen (2017) states that organizations establish legitimacy through social accountability, and that they thus engage with stakeholders for “normative reasons [that] appeal to underlying concepts such as …morality,” (p. 63), he is highlighting the relevance of culture in establishing credibility with stakeholder groups.

Filtering cognition of a message through the frame of culture is to apply “personal feelings and subjective associations” (Hallahan et al., 2007, p. 23) to the interpretation of the message. Hallahan et al. (2007) refer to this as the connotative meaning of a message and state that it “is the guiding factor in cognition and behavior” and should not be ignored (p. 23). The importance of accounting for connotative meaning in communications is reinforced by Expectancy Violation (EV) theory, which “was developed to explain the role of cultural norms in changing communication behaviors and postinteraction impressions…norms dictate the range of behaviors that are socially acceptable and create expectancies and violations of such expectations.” (Sohn & Lariscy, 2012, p. 15). Sohn and Lariscy (2012) found that the values and beliefs that an individual has about social norms play an important role in evaluating an organization’s reputation during a crisis related to social accountability, and that such crises are more likely to adversely impact an organization’s reputation, thereby establishing that the stakes are higher when it comes to “getting it right” with culturally appropriate messages.

Since “every aspect of an organization’s life has the potential to become an object of communication,” (Christensen et al., 2009, p. 210) all actions are effectively messages, and therefore, “companies communicate with everything they do” (Gronstedt as cited in Christensen et al., 2009, p. 210). In the quest for culturally competent communications, Strategic Communications practitioners must behave in a manner that conforms with local social norms, and those of stakeholders they engage with.

Culture, Cultural Competence, and Intercultural Mediators

Culture

In my research, I came across several definitions of culture from which I identified four common themes. These are that culture: 1) Is a set of norms and values that dictate guidelines for acceptable behavior within a group; 2) Is a lens, or frame through which messages are interpreted and meanings are shared within a group; 3) Varies through membership in different groups; and, 4) Is dynamic in the way that members of a group participate in it. These themes are reflected in the following definitions.

Hansen et al. (2011) define culture as a blueprint for living—consisting of values and norms—which “provides a lens through which individuals can interpret the world around them” (p. 245) [norms and lens theme]. They indicate that culture exists at multiple levels, “from broad supracultures comprising clusters of nations with similar economic systems, ethnicities, and religions, to narrow microcultures that exist within families and organizations” (p. 245) [membership variance theme]. Liddicoat and Kohler (2012) indicate that culture is a “frame” through which “meanings are conveyed and interpreted” (p. 76) [lens theme], and state that “culture is not simply a body of knowledge but rather a framework in which people live their lives and communicate shared meanings with each other” (p. 77) [norms theme]. In regard to culture variance by group membership, they state that “culture varies with time, place and social category, and for age, gender, religion, ethnicity and sexuality…people participate in different groups and have multiple memberships within their cultural group” (p. 77) [membership variance theme].

Griffith and Harvey (2001) differentiate between national culture and organizational culture—thereby distinguishing between two membership groups [membership variance theme]—stating that national culture consists of “the values, beliefs, and assumptions that define a distinct way of life of a group of people,” [norms theme] and that it “shapes how reality is interpreted in a society” (p. 89) [lens theme]. According to Griffith and Harvey, national culture impacts organizational culture, which is “reflected in the employees' attributes and understanding, policies and practices implemented, and overall conditions of the work environment” [norms and lens theme] (p. 90).

Overall (2009) states that culture “defines every aspect of human life including how humans think and create knowledge...knowledge is viewed as a dynamic process, which is socially constructed…cultural traditions and social practices regulate, express, and transform the way humans think” [norms, lens, and dynamic theme] (p. 180). Overall further adds that “thinking and culture are inseparable” (p. 181).

These definitions, and the earlier discussion about message cognition as a culture-referential process support the notion that culture and thinking are inseparable, Figure 1 is a helpful visualization of this perspective and serves as an antecedent to the theories I will cover on the acquisition of cultural competence.

Figure 1

Thinking and Culture

Note. This figure is based on Overall’s illustration on cultural competence (2009, p. 181)

Liddicoat and Kohler (2012) highlight that culture variability through differing group memberships is further compounded by the degree to which individuals exercise their culture, or participate in it [dynamic theme], as “people can resist, subvert or challenge the cultural practices to which they are exposed…individual members of a culture enact that culture differently and pay different levels of attention to the cultural norms that operate in their society…culture in this sense is dynamic [and] evolving” (p. 77).

Recognizing that culture is dynamic is a prevalent theme in developing cultural competence—a concept I will cover next—because culture is dynamic, by extension, so is cultural competence. Remembering this principle will help strategic communications practitioners to avoid the application of sophisticated stereotypes (Bird and Osland, 2006) when they don’t apply to a particular stakeholder or situation.

In summary, culture is a set of norms and values that dictate guidelines for acceptable behavior within a group, while providing a lens through which messages are interpreted and meanings are shared within a group; it varies through membership in different groups, it is dynamic in the way that members of a group participate in it, and as a result of these characteristics it is inseparable from thinking. Figure 2 illustrates these facets of culture and how they are relevant to the work of Strategic Communications practitioners seeking to communicate in a culturally competent way.

Strategic Communications practitioners must ensure that their messages conform to the cultural norms and values of their stakeholders, or that—at a minimum—they don’t violate them; they should adapt their messaging in anticipation of how they will be framed by a specific stakeholder group—culturally-relevant communication does not prescribe to a “one-size-fits-all” approach, messages must be tailored to the cultural context of the intended recipient(s).

Practitioners must also be aware of how membership in multiple groups (gender, age, profession, education level, ethnicity, etc.) may privilege some meanings over others in the minds of stakeholders when their message is interpreted; and, they must remember that messages that have been effective with a stakeholder group in the past may not be effective today because culture is always changing, which means that the same message may be interpreted differently at different times.

Figure 2

Culture and Communication

Note. These components are necessary for culturally competent messages, but this is not an exhaustive list. The goal is to show the characteristics of culture previously identified and what considerations they result in for the culturally competent communicator.

Cultural Competence

The concept of “cultural competence” or being “culturally competent” is referred to with a variety of terms in the literature I reviewed; these terms are “cultural competence,” (Johnson et al.; Liddicoat and Kohler, 2012; Overall, 2009) “globally competent,” (Johnson et al., 2006) 527), “intercultural competence,” (Bartel-Radic, 2006; Demangeot et al., 2013; Johnson et al., 2006) “cross-cultural competence,” (Johnson et al., 2006; Lakshman, 2013; Mor et al., 2013) “intercultural effectiveness,” (Mor et al., 2013) “multiculturalism,” (Cox, 1991) “cultural adaptation,” (Hansen et al., 2011) and “cultural understanding” (Barner-Rassmusen et al., 2014; Griffith & Harvey, 2001). For purposes of this research paper, I will use the term “cultural competence” when referring to this concept.

Cultural competence is defined broadly as an individual’s ability to adapt xyr behavior in order to communicate effectively with people of other cultures (Johnson et al., 2006; Demangeot et al., 2013). Overall (2009) presents a more detailed definition that summarizes the various components of cultural competence discussed by the research in my literature review. She defines cultural competence as “The ability to recognize the significance of culture in one’s own life and in the lives of others; and to come to know and respect diverse cultural backgrounds and characteristics through interaction with individuals from diverse linguistic, cultural, and socioeconomic groups; and to fully integrate the culture of diverse groups into services, work, and institutions in order to enhance the lives of both those being served…and those engaged in service” (p. 189- 190).

This definition covers the component of self-awareness, which is a requirement for the culturally competent communicator to look introspectively in order to understand: how culture frames one’s views and presentation of self; and that one’s reality isn’t an objective one, but one that is subjective to one’s own cultural understanding, such as values, beliefs, history, and traditions (Bird & Osland, 2006; Cox, 1991; Johnson, et al, 2006; Lakshman, 2013; Liddicoat & Kohler, 2012; Mor et al., 2013). It also includes the concept of recognizing how these factors frame the way others think and present themselves (Bird & Osland, 2006; Hansen et al., 2011; Johnson et al., 2006; Lakshman, 2013; Liddicoat & Kohler, 2012; Mor et al., 2013). Together, these skills of awareness make up the culturally competent communicator’s attributional complexity—the ability to understand the causes behind one’s own behavior and the behavior of others (Bird & Osland, 2006; Johnson et al., 2006; Lakshman, 2013) and are a form of metacognitive intelligence—the ability to think about and understand one’s own thought processes and that of others (Barner-Rassmusen et al., 2014; Hansen et al., 2011; Lakshman, 2013; Mor et al., 2013).

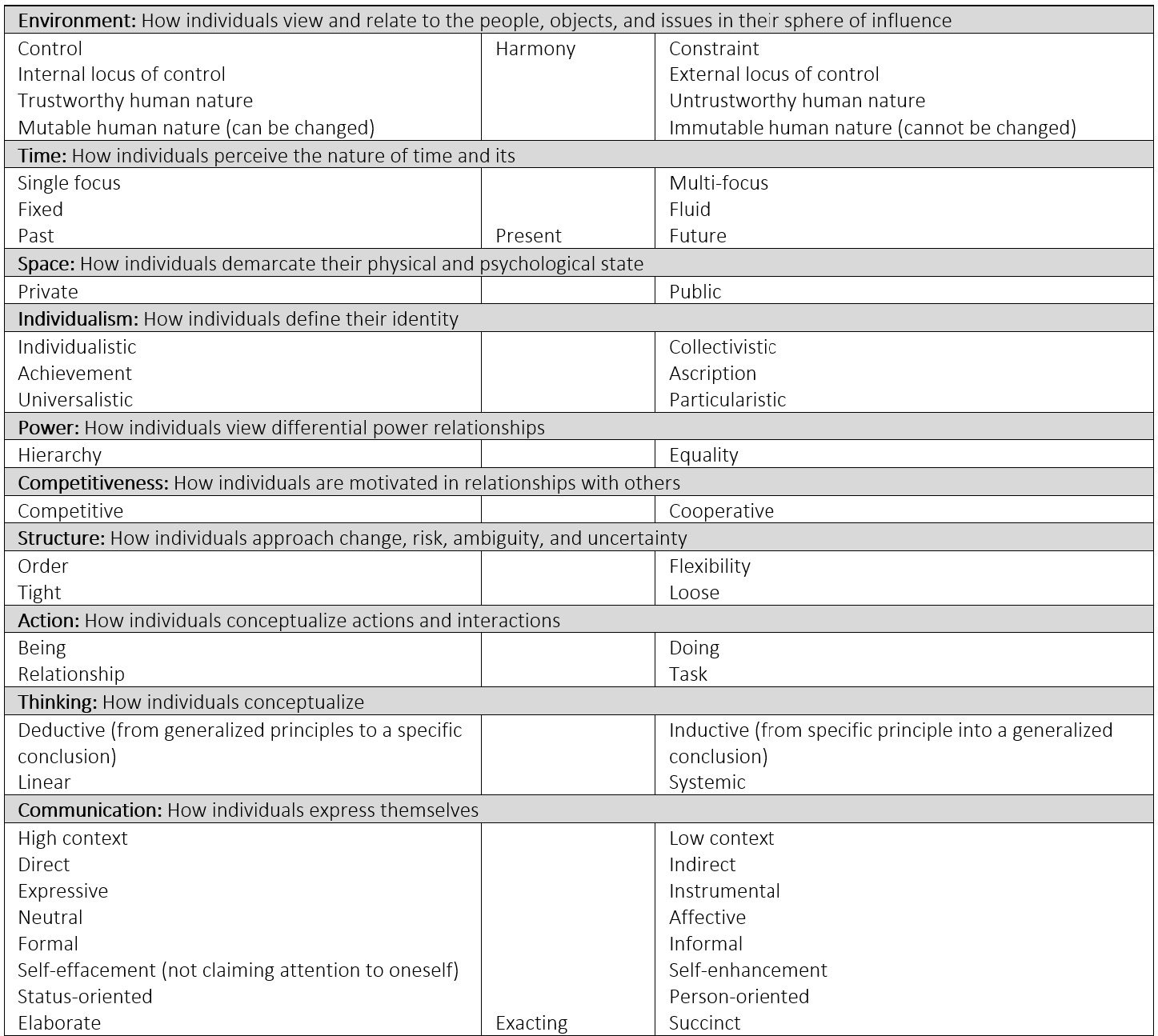

Another component that Overall’s (2009) definition touches on, “come to know…diverse cultural backgrounds and characteristics,” (p. 189) is the cultural knowledge that a culturally competent communicator must possess—this is knowing the similarities and differences between one’s culture and other cultures, and is a type of cognitive intelligence (Bird & Osland, 2006; Hansen et al., 2011; Johnson et al., 2006; Griffith & Harvey, 2001; Lakshman, 2013; Mor et al., 2013; Reyes et al., 2012). Bill and Osland (2006) provide a model, shown in Figure 3, that is helpful for gaining a better understanding of other cultures by outlining continuums, or dimensions, of cultural values; they highlight that while the dimensions “were developed to yield greater cultural understanding …they cannot explain everything about the complex nature of culture” (p. 118), so a person should not exclusively rely on this model to inform xyr intercultural communication efforts. They further state that “When these dimensions are used to reduce complex cultures to a shorthand description applied to all people from a particular culture, we call this sophisticated stereotyping… [which] can be helpful provided we acknowledge [its] limitations” (p. 119).

Overall’s (2009) definition also refers to a behavioral component of cultural competence, “to come to know… through interaction…and to fully integrate the culture of diverse groups into services, work” (p. 189-190). This component focuses on the behavior that will lead to cultural knowledge and on behaving and communicating in a way that exhibits cultural competence; it’s not just about having cultural knowledge, it’s about using it to inform and modify behavior in order to be more effective communicators (Bartel-Radic, 2006; Bird & Osland, 2006; Demangeot, 2013; Hansen et al., 2011; Johnson et al., 2006; Lakshman, 2013; Mor et al., 2013). Hansen et al. (2011) refer to this as “Behavioral Intelligence,” or “Behavioral CQ,” and explain it as follows, “Behavioral CQ encompasses the capability to exhibit appropriate verbal and nonverbal actions when interacting with people from a different culture. Individuals high in behavioral CQ are able to interact effectively across cultures based on their broad range of communication capabilities, such as exhibiting culturally appropriate words, tone, gestures, and facial expressions. These capabilities provide the means through which cognitive and metacognitive CQ can be applied” (p. 248).

Figure 3

Cultural Value Dimensions

Note. This is Bird and Osland’s (2006) Dimensions of Cultural Values model (p. 120 -121)

The behavioral component also requires that the culturally competent communicator continuously engage in intercultural social interaction in order to develop and maintain xyr cultural attributional awareness, (Bartel-Radic, 2006; Bird & Osland, 2006; Griffith & Harvey, 2001; Lakshman, 2013; Liddicoat & Kohler, 2012; Reyes et al., 2012) because culture is dynamic, as previously discussed, in that it varies from person to person—even within members of the same group (Liddicoat & Kohler, 2012). Research by Bartel and Radic (2006) found that engaging in intercultural social interaction “explains more than 50% intercultural learning. It is, in consequence, the most important, but not the only factor in intercultural learning” (p. 672). Griffith and Harvey (2001) explain that social interaction leads to bonding, which “involves reducing the ‘stranger’ orientation to another person from a different culture…thereby increasing communication satisfaction and over time building trust” (p. 95). Liddicoat and Kohler (2012) aptly summarize the concept of continuous learning as follows, “to be intercultural involves continuous intercultural learning through experience and critical reflection. There can be no final endpoint at which the individual achieves the intercultural state, but rather to be intercultural is by its very nature an unfinishable work-in-progress of action in response to new experiences and reflection on the action” (p. 81).

Liddicoat and Kohler’s use the concept of “being intercultural” to refer to the state of having cultural competence. As framed by them, the behavioral component of cultural competence aids in the acquisition of cognitive intelligence and in the honing of metacognitive intelligence by communications practitioners, the two previously discussed components of cultural competence.

Another component of cultural competence in Overall’s (2009) definition is affective, “The ability to…respect diverse cultural backgrounds… in order to enhance the lives of both those being served…and those engaged in service” (italicized for emphasis) (p. 189-190)—this refers to the feelings, personality traits, and attitudes that a communications practitioner must have in order to be culturally competent, as well as to the motivation “to direct and sustain effort toward functioning in intercultural situations” (Ang et al., 2015, p . 433). In Overall’s definition, she references an attitude of respect towards diverse cultural backgrounds, and the motivation to sustain an effort to function interculturally in order to improve the lives of those being served. According to researchers, personality traits such as flexibility, a positive attitude, caring, and empathy—are traits that are difficult to teach because they are acquired through long-term learning (Bartel-Radic, 2006; Demangeot et al., 2013; Hansen et al., 2011; Johnson et al., 2006; Lakshman, 2013; Mor et al., 2013). According to Johnson et al. (2006), these attributes are “antecedents that can either help or hinder the development of CC [(cultural competence)]” (p. 532), they add that these attributes “cannot easily be acquired by individuals who don't already possess them. This suggests that certain components of CC cannot easily be taught, and that certain individuals may have an aptitude for developing CC whereas others do not” (p. 535). This domain of the affective component of cultural competence is also referred to as “emotional intelligence” (Hansen et al., 2011; Johnson et al., 2006).

Hansen et al. define the motivation aspect of the affective domain of cultural competence as “the level of attention and energy the individual directs toward learning about and functioning in situations characterized by cultural differences,” (p. 248). This is often referred to as “motivational intelligence” (Ang et al, 2015; Hansen et al., 2011; Johnson et al., 2006; Mor et al., 2013). According to Ang et al. (2015), research on the cultural adjustment of sojourners and expatriates has shown that “motivational cultural intelligence is the strongest predictor of cultural adjustment” (p. 436). This means that in order for communications practitioners to be culturally competent, they must be motivated to use their cognitive and emotional cultural intelligence when communicating interculturally.

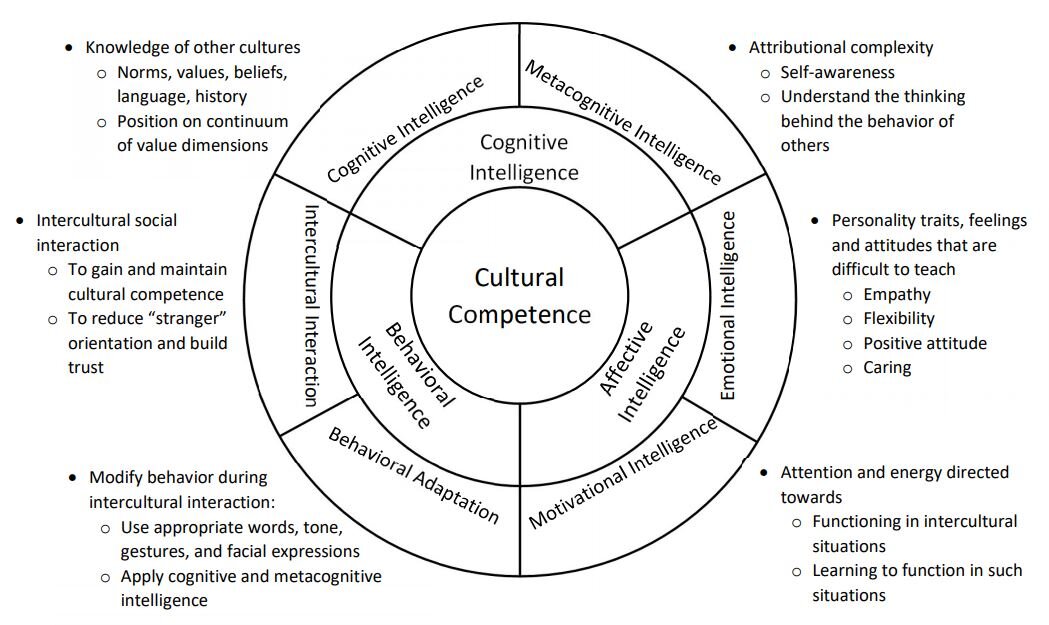

In summary, cultural competence has three domains—these are: the cognitive domain, which consist of cognitive intelligence (cultural knowledge) and metacognitive intelligence (thinking about how culture affects one’s own thinking and the thinking of others); the behavioral domain which consists continuous intercultural social interaction and behavioral adaptability in intercultural situations; and the affective domain, which consists of emotional intelligence (personal traits that are difficult to teach) and motivational intelligence (an individual’s drive to be effective in intercultural situations. This model of cultural competence and its three domains is shown in Figure 4. It provides a blueprint that Strategic Communications professionals can follow when seeking to communicate effectively in intercultural situations. Demangeot et al (2013) effectively summarize this model of cultural competence as follows, “Intercultural competency refers to the ability to successfully communicate with people of other cultures. Dominant theoretical models of intercultural competency across domains focus on three dimensions—cognition, affect, and behavior—making intercultural competency conceptually similar to an attitude. From a cognitive perspective, to exhibit intercultural competency means that a person has the ability to perceive and interpret information about a culture other than xyr own; from an affective perspective, it involves appropriate feelings, attitudes, and traits necessary to successfully interact with culturally different others; and from a behavioral perspective, it suggests that a person has the competencies and abilities to communicate effectively in cross-cultural inter-actions” (p. 158).

Intercultural Mediators

An “intercultural mediator” (IM) is described by Liddicoat and Kohler (2012) as “a person who can build bridges between understandings developed and communicated through different languages and cultures. Such mediators can interpret cultures for themselves and for others...That is, they stand between cultures and provide a bridge between them” (p. 79). Barner-Rassmusen et al., (2014) refer to these individuals as “boundary spanners,” and describe them as individuals who “are perceived by other members of both their own in-group and/or relevant out-groups to engage in and facilitate significant interactions between the two groups…They facilitate knowledge sharing and the development of collective social capital, effective collaboration, and value creation” (p. 887). According to Overall (2009), “professionals who are able to bridge an understanding of language differences are culturally competent” (p. 198). Demangeot (2013) states that “to exhibit intercultural competency means that a person has the ability to perceive and interpret information about a culture other than his or her own” (p. 158). Through my research, I found that IMs have higher levels of skill across the three domains of cultural competence: affective intelligence, behavioral intelligence, and cognitive intelligence (Barner-Rassmusen et al., 2014; Hansen et al., 2011; Johnson et al., 2006; Mor et al., 2013). I will highlight instances in which this was conveyed.

Figure 4

Cultural Competence Model

Note. Cultural competence is composed of three domains: cognitive, behavioral, and affective.

IMs have higher cognitive and behavioral ability in intercultural interactions. The intercultural success of intercultural mediators (IMs) corresponds with “mindfulness and self-awareness about cultural assumptions,” (Mor et al., 2013, p. 454) IMs “are consciously aware of others' cultural preferences before and during interactions. They also question cultural assumptions and adjust their mental models during and after interactions” (Mor et al., 2013, p. 454). According to Hansen et al. (2011), IMs “have a thorough understanding of the norms, practices, and conventions characterizing different cultures. They understand political and economic systems, institutions, and cultural values, and have advanced cognitive categorization schemes through which they can recognize similarities and differences across cultures” (p. 246). Cultural categorization schemes are a form of cognitive intelligence, or cultural knowledge structure, that encompass facts about a culture and information on appropriate behavior; they provide a means through which individuals can associate appropriate behavior to situations and adapt according to circumstances—their use can be seen as a combination of cognitive and behavioral intelligence in action (Hansen et al., 2011). IMs have more complex cultural categories because they “utilize a greater number of categories, have more distinct categories, and have a more elaborate hierarchical structure through which categories are linked together,” as a result of this, they are more effective in intercultural interactions. In contrast, individuals with low cultural competence “possess relatively nonhierarchical, flat cultural knowledge structures… [and have] few superordinate cultural categories and no subordinate categories providing detailed information at more specific levels” (Hansen et al., 2011, p. 247), resulting in greater risk for misunderstandings in intercultural interactions.

IMs are also more motivated to be effective in intercultural interactions, this falls within the affective domain of cultural competence. According to Lakshman (2013), IMs are more motivated to “create knowledge structures that will guide future action in response to appropriate cultural-environmental scenarios,” (p. 926) and to adapt to the challenges of intercultural interactions because of their high degree of self-efficacy and confidence. IMs are also better at handling ambiguity, as such, they are “more motivated to exert effort and master a challenge…[and are] better equipped to adapt to the challenges cross-cultural [interaction] presents” (italicized for emphasis) (Hansen et al., 2011, p. 248). Johnson et al. reinforce the concept of high motivation in IMs when they state that “an individual with a high level of cultural intelligence has…the motivational impetus to adapt to a different cultural environment… self-efficacy and perseverance [are] examples of personal characteristics that can foster motivation” (italicized for emphasis) (Johnson et al., 2006, p. 536-537).

IMs also demonstrate greater emotional aptitude—the second component of the affective domain of cultural competence—characterized by “personality traits, such as empathy, open-mindedness and emotional stability, [that] confer a higher intercultural competence…the acquisition of intercultural competence is encouraged by positive emotion and the desire to learn” (italicized for emphasis) (Bartel-Radic, 2006, p. 651). According to Mor et al., in order to be effective in intercultural collaborations, individuals must develop close working relationships with their counterparts, in such cases, emotional closeness—such as trust—is a result of higher metacognitive ability and is associated with creative collaboration in intercultural relationships (2013); the IM’s ability to have and elicit trust in intercultural relationships leads to greater collaboration. According to Overall (2009), “essential natural abilities of empathy, respect, understanding, patience, and nonjudgmental attitudes [are] required for…cultural proficiency” (p. 189); because IMs must be culturally-proficient in their role as mediators between cultures, it stands to reason that they have a high degree of the abilities that Overall references here.

Bicultural individuals are highly effective culturally competent IMs. “Literature on biculturals has identified a number of qualities they share, such as superior levels of cultural metacognition, higher intercultural effectiveness, and greater effectiveness on multicultural teams” (Lakshman, 2013, p. 923). For the purpose of this paper, when I refer to “bicultural individuals,” I am referring to individuals who: identify with two cultures; have internalized the beliefs, values, and norms of both cultures; speak, read, and write the language of both cultures (bilingual); and, can switch between cultural frames depending on situational cues (Barner-Rassmusen et al., 2014; Lakshman, 2013; Reyes et al., 2012).

The inclusion of bicultural language fluency and literacy in this definition is to refer to individuals that are “fully” bicultural, in the sense that “cultural reality is created through language, and the full meaning associated with a given concept cannot be accessed without in-depth knowledge of the language in its cultural context,” (Barner-Rassmusen et al., 2014, p. 890) since “oral and written language are embedded in a cultural system,” (Reyes et al., 2012, p. 308) and “the learning of a language forms a fundamental part of the development of intercultural understanding” (Liddicoat & Kohler, 2012, p.73), an individual cannot fully understand two cultures without being fluent in the language of each culture. Liddicoat and Kohler (2012) explain the important connection between language and culture as follows:

“At its most global level, culture constitutes a frame in which meanings are conveyed and interpreted, and it is at this level that culture is least apparently attached to language. Culture as context consists of the knowledge speakers have about how the world works, and how this is displayed, and understood, in acts of communication…such knowledge of the world is integrally associated with and invoked by language. This means that the message itself is not simply the sum of the linguistic elements of which it is composed but also includes additional elements of meaning that are invoked by, but not inherent in, the linguistic elements. Culture gives specific, local meanings to language by adding shared connotations and associations to the standard denotation of terms. In this way, culture can be understood as a form of community of practice, in which certain meanings are privileged above other possible meanings in ways that are relevant to the purposes and histories of the communities of practice. World knowledge is by its nature embedded and complex, but its operations can be seen through specific instances of communication in which assumed, shared world knowledge is fundamental to the message being communicated…discourse always represents a worldview — when language is used in communication, it is used within and for this worldview, and the worldview is as much constitutive of the message as are the linguistic forms and their agreed meanings” (p.77).

The absence of fluency in the language of a culture constitutes a significant deficiency in the understanding of connotative, “privileged” meanings in the messages shared by that culture through speech, music, literature, poetry, stories, and any other linguistic medium. Hence, I consider the bilingual individual to be more “fully” bicultural than an individual who may have internalized—to some degree (given xyr language limitations)—the cultural values and norms of two cultures but does not speak both languages.

Indeed, the higher degree of intercultural fluency in bilingual-bicultural individuals is reinforced by the more complex intercultural mediation work they are called on to do, as opposed to individuals who are bicultural, but not bilingual. According to Barner-Rassmusen (2014), “when mediating in intercultural situations, cultural and language skills influence the extent to which individual boundary spanners [(intercultural mediators)] perform four functions: exchanging, linking, facilitating, and intervening. Boundary spanners with both cultural and language skills perform more functions than those with only cultural skills, and language skills are critical for performing the most demanding functions. Key boundary spanners have properties that potentially make them not only valuable organizational human capital, but also rare and difficult to imitate” (p. 886).

Barner-Rassmusen et al. indicate that “Exchanging” refers to the collection and transmission of information in between culturally distinct groups; “linking” refers to connecting previously disconnected individuals across internal organizational boundaries in order to enable future intercultural collaboration; “facilitating” refers to IMs acting as a bridge through which “inter-group messages are delivered and interpreted…[this] may include explaining the often tacit narratives, codes of conduct, or behaviors of one group to the other, or framing arguments in ways that can be understood and accepted by the other group” (p. 888); and, “intervening” refers to resolving misunderstandings, managing conflict, negotiating, coordinating and building trust and relationships in intercultural interactions. The latter two functions—facilitating and linking—are the more demanding of the four and require that the IM be both culturally and linguistically competent because language provides “common cognitive ground” (p. 888) and contributes to mutual understanding (2014), as such bilingual-bicultural IMs are especially skilled at taking on these more complex functions of intercultural mediation.

The higher levels of cultural metacognition and intercultural effectiveness of biculturals are a result of their bicultural upbringing and the cognitive development of their bicultural identity. Lakshman (2013) calls this a “negotiated process” that involves “cognitive demands on the self to understand the value differences between the new and old cultures, and then adaptive integration of these differences to help form coping responses” (p. 929). According to Reyes et al., during childhood, biculturals develop “greater cognitive flexibility, including better creative and divergent thinking; a better ability to reorganize patterns and more flexibility in solving mental problems; and greater metasemiotic and metalinguistic awareness… [to recognize] when and how to use their two languages and cultures” (p. 313). As children, biculturals learn what language to use by associating it to specific contexts and social experiences, and often play a cross-language mediating role for their family, meaning their intercultural behavioral, metacognitive, and mediation skillsets develop since childhood. Bicultural children often participate in what Reyes et al. call “language brokering,” which consists of translating and interpreting across languages on behalf of their family; this work is key to connecting their family to the community and the institutions they interact with (Reyes et al., 2012). Biculturals are therefore better equipped at intercultural mediation because they have been mediating for their families through exchanging, linking, facilitating, and intervening since childhood.

Biculturals are furthermore adept at intercultural mediation due to their ability to code-switch—this is switching between languages, cultural frames, and behavior patterns in response to situational cues (Lakshman, 2013). Code-switching hence result in reducing cultural distance and the “stranger” or “other” orientation between the bicultural and xyr intended message recipient, helping to establish familiarity that is conducive to trust. Reyes et al. state that as children, biculturals use code-switching during “several discourse strategies, including translation, paraphrasing, use of paralinguistic cues, and gestures…used for language mediation during peer interactions and teacher-student classroom interactions” (2012, p. 319). During code-switching, biculturals are constantly switching between and adapting to different culture and language frames, this helps to them to develop a higher level of intercultural awareness that makes them especially adept IMs.

Biculturals are also more attributionally complex, meaning that they are “more accurate and faster in their judgments of social behaviors, and more accurate in their judgments of attitudes… in a cross-cultural setting…[this] contributes to cross-cultural competence and leadership effectiveness” (Lakshman, 2013, p. 931). According to Lakshman, this high level of attributional knowledge and complexity means that biculturals are less likely to exhibit bias and discrimination and are more likely to have tolerance and cultural sensitivity toward out-group members (2013).

The ability of intercultural mediators, especially biculturals, to build bridges that help establish trust between culturally distinct groups through the activities of exchanging, linking, facilitating and intervening is an indispensable resource for Strategic Communications teams seeking to influence culturally diverse stakeholders. My research has shown that bicultural intercultural mediators can serve as a strategic resource to organizations seeking to gain and expand their foothold in diverse marketplaces; their insight would lead to the development of messaging that resonates with diverse audiences and avoids the pitfalls of culturally insensitive approaches that are not just ineffective, but also damaging to organizational reputation. This highlights the importance of ensuring diversity in organizations and in the field of Strategic Communications. Strategies for diversity and inclusion are beyond the scope of this paper but are well documented in business journals—these strategies should be referenced for guidance by Strategic Communications managers seeking to support diversity in their teams.

Conclusion

Culturally competence is essential for effective communication. Recognizing that culture is a frame through which all messages are interpreted, when operating in an environment in which stakeholders are increasingly culturally diverse, culturally competent communication is more important than ever. Communications practitioners should familiarize themselves with the cognitive, behavioral, and affective domains of cultural competence and focus on fostering and utilizing the skills of intercultural mediators in order to achieve culturally competent communication. As stakeholders become more culturally diverse, cultural competence will become an even more critical skill in the field of Strategic Communications. Communications teams and organizations will benefit greatly from the ability of bilingual-bicultural communications actors to perform the functions of exchanging, linking, facilitating, and intervening in an intercultural stakeholder environment.

References

Ang, S., Rockstuhl, T., & Tan, M. L. (2015). Cultural intelligence and competencies. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 433–439. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.25050-2

Barner-Rasmussen, W., Ehrnrooth, M., Koveshnikov, A., & Mäkelä, K. (2014). Cultural and language skills as resources for boundary spanning within the MNC. Journal of International Business Studies, 45(7), 886–905. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43653735

Bartel-Radic, A. (2006). Intercultural learning in global teams. Management International Review, 46(6), 647–678. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40836111

Bird, A., & Osland, J. S. (2005). Making sense of intercultural collaboration. International Studies of Management & Organization, 35(4), 115–132. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40397648

Brown, A., & Lopez, M. H. (2019, December 30). Mapping the Latino population, by state, county and city. Retrieved February 15, 2020, from https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2013/08/29/mapping-the-latino-population-by-state-county-and-city/

Byram, M. (2003). On being 'bicultural' and 'intercultural'. In Intercultural experience and education (pp. 50–66). Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters.

Christensen, L. T., Fırat, A. F., & Cornelissen, J. (2009). New tensions and challenges in integrated communications. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 14(2), 207–219. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/13563280910953870

Cornelissen, J. (2017). Corporate Communication: A Guide to Theory and Practice. London: SAGE Publications.

Cox, T. (1991). The multicultural organization. Academy of Management, 5(2), 34–47. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4165006

Demangeot, C., Adkins, N. R., Mueller, R. D., Henderson, G. R., Ferguson, N. S., Mandiberg, J. M., … Zúñiga, M. A. (2013). Toward intercultural competency in multicultural marketplaces. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 32(Special Issue), 156–164. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43305324

Griffith, D. A., & Harvey, M. G. (2001). Executive insights: An intercultural communication model for use in global interorganizational networks. Journal of International Marketing, 9(3), 87–103. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25048861

Hallahan, K., Holtzhausen, D., Ruler, B. V., Verčič, D., & Sriramesh, K. (2007). Defining Strategic Communication. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 1(1), 3–35. doi: 10.1080/15531180701285244

Hansen, J. D., Singh, T., Weilbaker, D. C., & Guesalaga, R. (2011). Cultural intelligence in cross-cultural selling: Propositions and directions for future research. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 31(3), 243–254. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41307392

Johnson, J. P., Lenartowicz, T., & Apud, S. (2006). Cross-cultural competence in international business: Toward a definition and a model. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(4), 525–543. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3875168

Lakshman, C. (2013). Biculturalism and attributional complexity: Cross-cultural leadership effectiveness. Journal of International Business Studies, 44(9), 922–940. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43653703

Lange, D. M., Lee, P. M., & Dai, Y. M. (2011). Organizational Reputation: A Review. Journal of Management, 37(1), 153–184. doi: 10.1177/01492063103390963

Liddicoat, A. J., & Kohler, M. (2012). Teaching Asian languages from an intercultural perspective: Building bridges for and with students of Indonesian. In X. Song & K. Cadman (Eds.), Bridging Transcultural Divides (pp. 73–99). Adelaide, Australia: University of Adelaide Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.20851/j.ctt1sq5w6k.9

Mor, S., Morris, M. W., & Joh, J. (2013). Identifying and training adaptive cross-cultural management skills: The crucial role of cultural metacognition. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 12(3), 453–475. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43696578

Overall, P. M. (2009). Cultural competence: A conceptual framework for library and information science professionals. The Library Quarterly, 79(2), 175–204. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/597080

Reyes, I., Kenner, C., Moll, L. C., & Orellana, M. F. (2012). Biliteracy among children and youths. Reading Research Quarterly, 47(3), 307–327. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43497522

Sohn, Y. J., & Lariscy, R. W. (2012). A “Buffer” or “Boomerang?”— The Role of Corporate Reputation in Bad Times. Communication Research, 1–23. doi: 10.1177/0093650212466891

State of California Health & Human Services Agency, Department of Healthcare Services. (2017). Standards for determining threshold languages and requirements for section 1557 of the affordable care act (All Plan Letter 17-011). Sacramento, California.